-40%

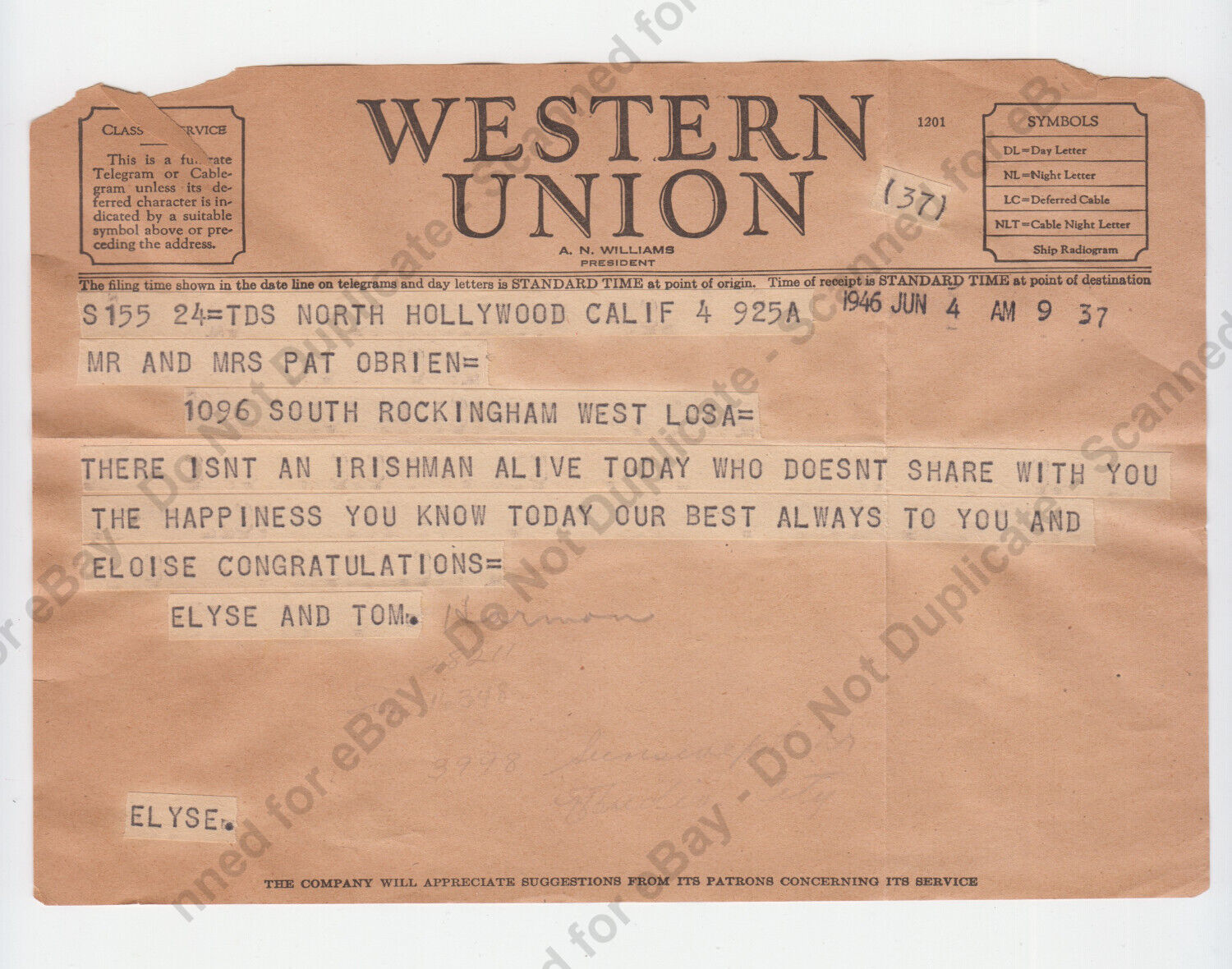

Elyse and Tom Harmon Western Union telegram 1946 (parents of Mark Harmon NCIS)

$ 31.67

- Description

- Size Guide

Description

Elyse and Tom Harmon Western Union telegram 1946 (parents of Mark Harmon NCIS)Size: 8” X 5 ½” / Unique Characteristics: Date stamped “1946 JUN 4 AM 9 37” Signed “Elyse and Tom” (Name ‘Harmon’ penciled-in by recipient Eloise O’Brien).

I've never believed in collecting for it's own sake. Collectors items should be shared and circulated. I grew up among my entertainment heroes of the Golden Age of Hollywood, and am now selling-off some of the treasures I accumulated as a fortunate young man in 1970s Tinsel Town.

The items I'm selling here have never been on the market before.

Tom Harmon

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Thomas Dudley Harmon (September 28, 1919 – March 15, 1990), known as Tom Harmon, as well as by the nickname "Old 98", was an American football player, military pilot, actor, and sports broadcaster.

Harmon grew up in Gary, Indiana, and played college football at the halfback position for the University of Michigan from 1938 to 1940. He led the nation in scoring and was a consensus All-American in both 1939 and 1940 and won the Heisman Trophy, the Maxwell Award, and the Associated Press Athlete of the Year award in 1940. He was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1954.

During World War II, Harmon served as a pilot in the U.S. Army Air Forces. In April 1943, he was the sole survivor of the crash of a bomber he piloted in South America en route to North Africa. Six months later, while flying a P-38 Lightning, he was shot down in a dogfight with Japanese Zeros near Kiukiang in China.

After the war, Harmon played two seasons of professional football for the Los Angeles Rams and had the longest run from scrimmage during the 1946 NFL season. He later pursued a career in sports broadcasting and was the play-by-play announcer for the first televised Rose Bowl in the late 1940s and worked for CBS from 1950 to 1962. He later hosted a 10-minute daily sports show on the ABC radio network in the 1960s and worked as the sports anchor on the KTLA nightly news from 1958 to 1964. He also handled play-by-play responsibility on broadcasts of UCLA football games in the 1960s and 1970s.

Early life

Harmon was born in Rensselaer, Indiana, at the family home at 118 South Weston Street, the son of Illinois natives Rose Marie (née Quinn) and Louis A. Harmon (1873–1948), a real estate agent.[2] Harmon had five older siblings, Louella, Harold, Mary, Louis, and Eugene, all born in Indiana. His maternal grandparents were Irish, while his father was of French, German, and Irish descent.

In 1924, the family moved to Gary, Indiana. At the time of the 1930 U.S. Census, the family was living at 578 Van Buren in Gary, where Harmon's father was employed as a real estate salesman, and his mother was employed as a clerk for the Census Bureau.

Harmon's three older brothers all excelled in athletics before him: Harold was a track star at Purdue University, Louis played basketball at Purdue, and Eugene was the captain of Tulane University's basketball team.

Harmon attended Horace Mann High School in Gary, graduating in 1937. He received 14 varsity letters in 10 sports at Horace Mann. He won the Indiana state championship both in the 100-yard dash and 220-yard low hurdles and won the national interscholastic scoring championship in football with 150 points. He ran the 100-yard dash in 9.9 seconds (half a second slower than Jesse Owens' world record) and 220-yard low hurdles in 22.6 seconds. He was also a star basketball player and threw two no-hitters as a pitcher in AAU baseball.[8] Michigan athletic director Fielding H. Yost in 1937 proclaimed Harmon "the greatest high school athlete of the year".

University of Michigan

At the urging of his high-school coach Douglass Kerr, who played end for Michigan in 1927 and 1928, Harmon enrolled at the University of Michigan in 1937. He played on the freshman football team that fall,[12] while the varsity compiled a 4–4 record in its final season under head coach Harry Kipke. In November 1937, the Associated Press published a story that Tulane coach Bill Bevan had tried to lure Harmon to transfer to that school, where his older brother was a student-athlete. Harmon chose to remain at Michigan, leading the varsity football team to a 19–4–1 (.813) record over the next three years.

In addition to football, Harmon was also a member of the basketball team for two years. He majored in English and speech at Michigan, aspiring to become a sports broadcaster, and, as a junior and senior, hosted a 15-minute program on the university radio station on Fridays.

1938 season

In 1938, Michigan hired Fritz Crisler as its new football coach. As a sophomore, Harmon started seven of eight games at the right halfback position . He gained 405 rushing yards, averaging more than five yards per carry, and also completed 21 of 45 passes for 310 yards with only one interception. With Crisler as the coach, Harmon in the backfield, and consensus All-American Ralph Heikkinen at the guard position, the Wolverines lost only one game, a 7–6 loss to Minnesota, and improved their record to 6–1–1.

Harmon began to draw national press coverage in the fourth game of the 1938 season, as he led a second-half comeback against Yale. After losing to Minnesota in the third week of the season, the Wolverines trailed Yale 13–2 at halftime. Harmon set up Michigan's first touchdown with a pass to Norman Purucker in the third quarter and then led the Wolverines on their final drive late in the fourth quarter. The United Press described the game-winning drive as follows:

Michigan seemed to be fighting for a hopeless cause and the hand crawled around the clock toward the end of the game. In that moment of despair for all those who cheer for Michigan, Harmon came out of nowhere to dominate the field. When the Yale line braced on its own goal, Harmon gambled by waiting patiently with the ball in his hand until John Nicholson could get free to catch the pass that meant defeat for Yale.

Harmon continued to draw accolades the following week, as Michigan defeated Illinois by a 14–0 score. In the first quarter, Harmon ran for the Wolverines' first touchdown, "twisting and pushing his way the last few yards".[20] He then "rifled" a pass to Forest Evashevski in the third quarter for Michigan's second touchdown.

In the final game of the 1938 season, Harmon led Michigan to an 18–0 victory over Ohio State in Columbus, Ohio, a game that was said to be the "climax of the Wolverines' return as a major gridiron power". Michigan had suffered four consecutive shutouts at the hands of the Buckeyes prior to the 1938 game. In the first quarter, Harmon ran for a touchdown, tallying Michigan's first points against Ohio State since 1933. In the fourth quarter, Harmon threw a 15-yard pass to Ed Frutig for Michigan's second touchdown.

At the end of the 1938 season, Harmon, described as "Michigan's sophomore sensation", won first-team honors on the United Press All-Big Ten Conference team. Harmon and teammate, Forest Evashevski, also won first-team all-conference honors from the Associated Press, becoming the first sophomores to be so honored since 1934.

1939 season

As a junior in 1939, Harmon started at the right halfback position in seven of eight games. The Wolverines compiled a 6–2 record, with losses to Illinois and Minnesota, and were ranked number 20 in the final AP poll. For the season, Harmon rushed for 868 yards on 129 carries in eight games, an average of 6.7 yards per carry. His average of 108.5 yards per game was the best in the NCAA during the 1939 season, more than 20 yards higher than any other player (runner up John Polanski of Wake Forest averaged 88.2 rushing yards per game). He also led the nation in scoring with 102 points on 14 touchdowns, 15 extra points, and one field goal.

In the second game of the season, a 27–7 victory over Iowa, Harmon scored every point for Michigan, including four touchdowns and three extra points. His longest run of the day was for 91 yards. The Associated Press called it one of the most amazing individual performances seen in the Big Ten since the days of Red Grange, describing Harmon "[d]arting, dodging and twisting up and down the chalk lines like a ballet dancer". After the game, Michigan coach Crisler praised Harmon's all-around contributions:

Harmon has everything. He's best known as a runner, but I'd say his blocking and defensive work are equally good. . . . He has a wonderful change of pace and can dodge and cut on a dime.

In the third game of the season, an 85–0 victory over Chicago, Harmon ran 57 yards for a touchdown and threw touchdown passes to Forest Evashevski and Bob Westfall before being taken out of the game for the second- and third-string backfield.

In Michigan's fourth game, a 27–7 victory over Yale, Harmon scored three touchdowns, kicked three extra points, and gained 203 yards on 18 carries. His longest gain of the day was a 59-yard touchdown run on a reverse play around the left end.

In the final game of the 1939 season, Michigan defeated an Ohio State team that was ranked number six in the country. After the Buckeyes took a 14–0 lead in the first 10 minutes, Harmon led the Wolverines to a comeback victory by a 21–14 score. In the second quarter, Harmon threw a 49-yard pass to Joe Rogers and then connected with Evashevski for the touchdown. In the third quarter, Harmon scored Michigan's second touchdown on a run around the right end. With 50 second remaining in the game, Harmon faked a field goal attempt as the holder picked up the ball and ran 24 yards for a touchdown behind Harmon's blocking. Harmon also kicked all three extra points for Michigan.

At the end of the 1939 season, Harmon was selected as Michigan's most valuable player, and he was a consensus pick for the 1939 College Football All-America Team, receiving first-team honors from, among others, the All-America Board, the Associated Press, Collier's Weekly, the International News Service, Liberty, Newsweek, the Sporting News, the United Press, Boys' Life, the Central Press Association, and Life. He also finished second in the voting for the 1939 Heisman Trophy, garnering 405 votes, while Nile Kinnick won the award with 651 votes.

1940 season

As a senior, Harmon started all eight games for Michigan, seven at left halfback and one at right halfback. The 1940 Michigan team compiled a 7–1 record, losing to national champion Minnesota by one point, and finished the season ranked number three in the final AP poll. For the season, Harmon rushed for 844 yards on 186 carries, an average of 4.5 yards per carry and 105.5 yards per game. For the second straight year, he also led the country in scoring with 117 points on 16 touchdowns, 18 extra points, and one field goal.

In the opening game of the 1940 season, Michigan defeated California by a 41–0 score. While celebrating his 21st birthday, Harmon scored four touchdowns, kicked four extra points, and threw a touchdown pass to David M. Nelson. Harmon's first touchdown came on the opening kickoff, which he returned 94 yards. His second touchdown came in the second quarter on a 72-yard punt return in which he reportedly dodged and swerved from one side of the field to the other, running about 100 yards before reaching the end zone. His third touchdown was on an 85-yard run in the second quarter. During the third touchdown run, a spectator jumped from the stands and ran onto the field trying to tackle Harmon. Even the 12th man, who was escorted off the field by police, could not stop Harmon from reaching the endzone. The Associated Press wrote that Harmon found California's defense "about as strong as a wet paper bag", noted that Harmon was "as hard to snare as a greased pig", and opined that the only reason Michigan's point total was not higher was that "Michigan's first-string players ran themselves into a complete state of exhaustion." After his performance against California, Fritz Crisler called Harmon "the greatest player I've ever coached".

In the second week of the season, Harmon, in a performance described by the Associated Press as "virtually a one-man show", ran for all three Michigan touchdowns and kicked all three extra points in a 21–14 victory over Michigan State. He increased his scoring total to 49 points after two games.

In the third week of the season, Michigan defeated Harvard by a 26–0 score, and Harmon increased his scoring total to 69 points, as he ran for three touchdowns, passed for another touchdown, and kicked two extra points. The United Press reported that the "smooth-gaited" Harmon "thrilled the spectators for more than three periods with brilliant dashes", and left the game in the fourth quarter to "tremendous applause" from the fans in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

In the season's fourth game, as Michigan defeated Illinois, 28–0, Harmon increased his point total to 80 as he ran for a touchdown and kicked a field goal and an extra point.

In Michigan's fifth game, Harmon played all 60 minutes and was responsible for both touchdowns in a 14–0 victory over a previously unbeaten Penn team featuring the country's second-leading scorer, Frank Reagan. Harmon ran 20 yards on a lateral from Evashevski for the first touchdown and passed 15 yards to Ed Frutig for the second. Harmon also kicked both of Michigan's extra points.[43] He was responsible for 155 yards from scrimmage, played the second half with his shirt "half ripped off his back", and reportedly "gave the dogged Quaker defense a going over that will never be forgotten".

In the sixth game, Michigan suffered its only loss to Minnesota. Playing on a wet and slippery field, Harmon completed 9 of 14 passes, despite throwing what was described as "a bar of slippery soap", including a touchdown pass to Evashevski. Harmon missed the extra point kick that left Michigan trailing 7–6. Harmon later recalled: "It makes me sick to think of the chances we blew that day. We should have beaten them by four or five touchdowns. They're a good club, but we're better, and so is Northwestern."

In his final college football game, Harmon led the Wolverines to a 40–0 victory over Ohio State, scoring three rushing touchdowns, two passing touchdowns, and four extra points, and intercepting three passes, and punting three times for an average of 50 yards. In a display of sportsmanship and appreciation, the Ohio State fans in Columbus gave Harmon a standing ovation at game's end. No other Wolverine player has been so honored, before or since.

At the end of the 1940 season, Harmon won numerous awards, including:

On November 25, 1940, the Maxwell Memorial Club announced that Harmon had been chosen as the winner of the Maxwell Award as "the nation's No. 1 football player for 1940".

On November 28, 1940, Harmon was announced as the winner of the Heisman Trophy as the country's outstanding college football player with a record count of 1,303 votes.

On December 10, 1940, Harmon was named the male athlete of the year across all sports in annual polling of sports experts conducted by the Associated Press. Harmon received 147 points in the poll, nearly tripling the points received by runner-up Hank Greenberg.

Harmon was also a unanimous All-American, receiving first-team honors from the All-America Board, the Associated Press, Collier's Weekly, the International News Service, Liberty magazine, the Newspaper Enterprise Association, Newsweek, the Sporting News, and the United Press.

In mid-December 1940, Harmon was unanimously selected as the most valuable player in the Big Ten Conference.

Harmon and backfield teammate Forest Evashevski, described as Michigan's "two-man gang", were both selected by conference coaches for the third consecutive year as first-team players on the Associated Press All-Big Ten Conference team.

Career statistics and legacy

In his three seasons at Michigan, Harmon rushed for 2,151 yards on 399 carries, completed 101 of 233 passes for 1,396 yards and 16 touchdowns, and scored 237 points. During his career, he played all 60 minutes eight times. Harmon also scored 33 touchdowns, breaking Red Grange's collegiate record of 31 touchdowns. He led the nation in scoring in both 1939 and 1940 (a feat that remains unmatched). His career average of 9.9 points per game stood as an NCAA record for ten seasons.

Harmon was inducted into the College Football Hall of Fame in 1954, the Michigan Sports Hall of Fame in 1962, the Indiana Football Hall of Fame in 1974, and the University of Michigan Athletic Hall of Honor (as one of five inaugural inductees) in 1978. In 2007, Harmon was ranked 16th on ESPN's Top 25 Players in College Football list. Harmon was also ranked fifth on the Big Ten Network's program "Big Ten Icons", honoring the greatest athletes in the Big Ten Conference's history.

In November 1940, Michigan's equipment manager announced that Harmon's jersey number, 98, would be retired when Harmon played his last game. About 73 years later, Michigan unretired Harmon's jersey as part of its Michigan Football Legends program. During a ceremony in September 2013, Harmon was honored as a Michigan Football Legend, and Devin Gardner was chosen as the first Michigan player since 1940 to wear the jersey.

Professional football and movies

In December 1940, Harmon was selected by the Chicago Bears with the first selection in the first round of the 1941 NFL Draft. However, Harmon declined to sign with the Bears, initially stating that he was through playing football and instead planned to pursue a career in radio and the movies.

In March 1941, Harmon signed a contract with Columbia Pictures to star in a motion picture, titled Harmon of Michigan, with filming set to commence in July 1941, after Harmon graduated from Michigan. The film was released later that year. His film appearances included two Paramount Martin and Lewis comedies as a sports announcer, That's My Boy (1951) and The Caddy (1953).

On October 10, 1941, the New York Americans of the rival American Football League announced that they had signed Harmon to play in the final four games of the 1941 season for around ,500 per game.[69]

Military service

In May 1941, the draft board in Lake County, Indiana, announced that Harmon had been classified as 1-B and deferred as a student until July 1, 1941. In July 1941, Harmon was granted a further 60-day deferment based on his claim that he was the sole support for his parents. In September 1941, he appeared in front of the draft board seeking a permanent deferment. His request was denied, and he was classified as 1-A. Harmon, then working as a radio announcer in Detroit, stated that he intended to appeal the ruling. His appeal was denied in October 1941, and he was given until November 1941 to enlist.

Harmon applied to enlist as a cadet in the United States Army Air Corps in early November 1941. He was granted permission to enlist as a cadet in March 1942. Despite rumors that he had washed out of flight school, Harmon underwent his first 60 hours of flight training at the now defunct Oxnard Air Force Base in Camarillo, California, and then finished basic flying school at Gardner Army Airfield in Taft, California, in September 1942. He was commissioned as a second lieutenant and a twin-engined bomber pilot and assigned to Williams Field in Arizona in October 1942.

In April 1943, an Army bomber piloted by Harmon, and nicknamed "Old 98" after Harmon's football jersey number, crashed into the South American jungle while en route to North Africa. Harmon reported that he had been flying through heavy rain turbulence for two hours. When Harmon tried to fly the plane to an opening in the weather, there was a sharp crack from the right wing and engine, and Harmon was unable to pull the plane from a steep dive. After ordering his crew to bail out, Harmon parachuted from the plane at 1,500 feet. He ended up in a tree 20 yards from where his plane crashed. Out of a crew of six, Harmon was the sole survivor of the crash and spent several days working his way through jungle and swamp. He ultimately came upon natives in Dutch Guiana who escorted him in a dugout canoe to a village, where he was taken by outrigger canoe to a base of the Antilles Air Command.

After a brief assignment as a Lockheed P-38 Lightning pilot in North Africa, Harmon was assigned to duty with the 449th Fighter Interceptor Squadron in China in the summer of 1943. In October of that year, while escorting bombers on a low-level mission over Kiukiang, Harmon's P-38 was shot down over the Yangtze River by a Japanese Zero during a dogfight. According to some accounts, Harmon shot down two Zeros in a dogfight over the Kiukiang docks and warehouses. Harmon was forced to bail out into Japanese-occupied China. He was later rescued by anti-Japanese Chinese guerrillas. Harmon was awarded the Purple Heart and the Silver Star for his actions with the 449th Fighter Squadron.

Harmon returned from China in January 1944. In November 1944, Harmon's account of his war service was published by Thomas Y. Crowell Company under the title, "Pilots Also Pray". He was promoted to the rank of captain in April 1945, and he was discharged from the military at the end of the war on August 13, 1945.

Postwar career

Return from service

In August 1945, upon his discharge from the military, Harmon joined the college all-star team to play against the NFL champions (the Green Bay Packers) in the annual College Football All-Star Classic in Chicago. Although the Packers defeated the college all-star team by a 19–7 score, Harmon provided a highlight with a 76-yard kickoff return that set up the all-stars' only touchdown. Harmon also kicked the extra point.

Even before his playing days had ended, Harmon had begun to pursue a career in broadcasting. Before joining the military, he worked as the sports editor for WJR radio in Detroit. In September 1945, Harmon returned to Detroit's WJR radio to broadcast Michigan football games for the 1945 season. In October 1945, Harmon was hired to do a Saturday evening sports-feature program to be broadcast on the Mutual Radio Network. He said at the time that his playing days were behind him and that he intended to move to California after the football season was over.

Los Angeles Rams

Harmon's retirement from football was short-lived. In July 1946, he signed a two-year contract to play professional football for the Los Angeles Rams.[93] Harmon later recalled that his return to the playing field was reluctant and made necessary by a ,000 tax bill he received for his prewar earnings.

A "series of injuries to war-weakened muscles" hampered his comeback.[94] He appeared in 10 games for the Rams during the 1946 NFL season, rushing for 236 yards on 47 carries, and catching 10 passes for 199 yards. He had an 84-yard run against the Chicago Bears on October 14, 1946, that was the longest in the NFL in 1946.[94][95] He also gained 135 yards on 18 carries in a 1946 game against the Green Bay Packers.[94] The following year, Harmon appeared in 12 games for the Rams, gaining 306 rushing yards on 60 carries, and catching five passes for 89 yards.

Harmon believed that his talents did not fit with the T-formation offense run by the Rams, and having broken his nose 13 times, he retired for good from his playing career after the 1947 season.[16][95] Harmon later recalled that he went from a ,500-a-week job as a player to a 0-a-week position as an announcer in Glendale, California.

Broadcasting career

After retiring as a player in 1947, Harmon returned to his career as a sports broadcaster, becoming one of the first and most successful athletes to make the transition from player to broadcaster.[16] Harmon attributed his successful career in radio and television to the early education he received from his drama teacher, Mary Gorrell, at Horace Mann high school. During the 1948 season, he broadcast Rams' games for KFI radio in Los Angeles. In the late 1940s, he was the play-by-play announcer for NBC on the first television broadcast of a Rose Bowl Game.[9] From around 1950 to 1962, Harmon worked as a sportscaster for the CBS network.[96] He also handled the nightly sport report on KTLA television in Los Angeles from 1958 to 1964.

In 1962, Harmon joined the sports staff of the ABC radio network. He developed a concept for a 10-minute daily sports program. He hired the crew, purchased the equipment, found sponsors, and then sold the program to ABC.[97] His 10-minute broadcasts became a staple of the ABC radio network. By 1965, his company, Tom Harmon Sports, was generating annual gross revenue of million and had six full-time employees.

In the early 1970s, Harmon was the spokesman in television commercials for Kellogg's Product 19 cereal. He also worked as the play-by-play announcer for UCLA Bruins football games on KTLA during the 1960s and 1970s. In his later years, he was the host of Raider Playbook on KNBC in Los Angeles and also handled play-by-play responsibility for Los Angeles Raiders' preseason games.

Family

Actress Elyse Knox, who was married to Harmon in 1944

In August 1944, Harmon married actress and model Elyse Knox in a ceremony at St. Mary's student chapel at the University of Michigan. Harmon saved his silk parachute from the crash of his P-38, and it was used as the material for his wife's wedding dress. The couple had three children:

Kristin Harmon Nelson (June 25, 1945 - April 27, 2018), was born in Burbank, California, where Harmon was stationed at the time. She married recording artist Ricky Nelson in 1963. Harmon joked in the mid-1960s that he was then known as "Ricky Nelson's father-in-law". Kristin worked as an actress and primitive artist and had four children: Tracy Nelson, twins Gunnar and Matthew Nelson, and Sam.

Kelly Harmon (born November 9, 1948) was a model, and later an interior designer. She married automaker John DeLorean in 1969. She later married Sports Illustrated publisher Robert Miller in 1984.

Mark Harmon, born in 1951, played college football for the UCLA Bruins before becoming a film and television actor. A Golden Globe and Emmy Awards nominee, he was chosen as People's "Sexiest Man Alive" in 1986, and is best known for his roles in the television series St. Elsewhere, Chicago Hope, and NCIS. He married actress Pam Dawber in 1987, and they have two sons.

Death

On March 15, 1990, Harmon suffered a heart attack at the Amanda Travel Agency in West Los Angeles after winning a golf tournament at Bel Air Country Club. He was taken to UCLA Medical Center, where he died at age 70.